00352 - 27 28 15 38 | mycon@mycon.lu

BEST PRACTICE GUIDE ON ASBESTOS

CONTENTS

4 MATERIALS CONTAINING ASBESTOS

4.1 Introduction

4.2 What they should do

5 RISK ASSESSMENT AND WORK PLAN BEFORE CARRYING OUT WORK

5.1 Introduction

5.2 What you must do

5.3 Template for a work plan checklist

6.1 Necessary decisions

6.2 Guidance on decisions on asbestos-containing materials in buildings

6.3 decisions regarding the notifiability of work

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Content of the training

7.3 Training programme - your task

7.4 Information

8.1 Equipment

8.2 Maintenance of the equipment

8.3 Your task

9 GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR MINIMISING EXPOSURE

9.1 General consideration

9.2 Your task

10 JOBS THAT MAY INVOLVE ASEBSTEXPOSURE

11 LOW-RISK WORK WITH ASBESTOS

11.1 Definition of low-risk work

11.2 General procedures for low-risk work

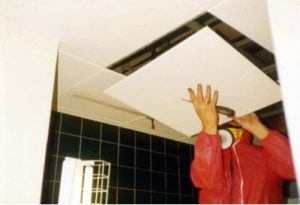

11.3 Examples of low-risk work

12 REPORTABLE WORK WITH ASBESTOS

12.1 Introduction

12.2 General procedures for notifiable work

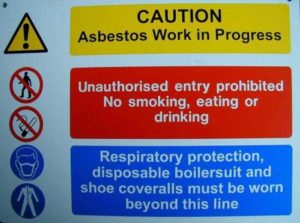

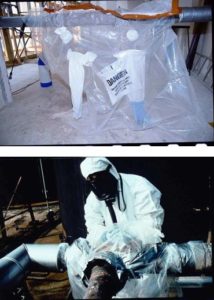

12.3 Enclosure for the performance of asbestos removal work

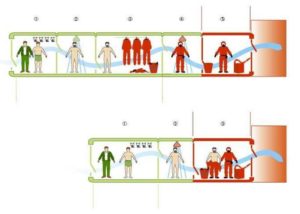

12.4 Decontamination of persons

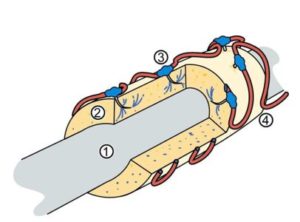

12.5 Dust suppression techniques

12.6 Encapsulation and housing

12.7 Inspection, monitoring and maintenance of the enclosure

12.8 Waste disposal

12.9 Cleaning and completion of the work

14 THE EMPLOYEE AND THE WORKING ENVIRONMENT

14.1 Introduction

14.2 The employee

14.3 The nature of the work

14.4 The working environment

15.1 Introduction

15.2 Problems

15.3 Recording the transport

15.4 What they should do

16 MONITORING AND MEASUREMENTS

16.1 Introduction

16.2 Indoor air sampling and methods of analysis for the samples

16.3 Aims of air monitoring

16.4 Selection of a monitoring organisation

16.5 What they should do

16.6 Information

17.1 Who else is involved?

17.2 Participation in the planning of the asbestos work

17.3 Retained asbestos-containing materials

17.4 Re-reference

17.5 What they should do

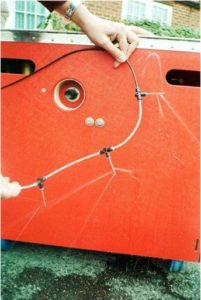

18 ASBESTOS IN OTHER PLACES (VEHICLES, MACHINES, ETC.)

18.1 Introduction

18.2 Variety of applications

18.3 Procedures to avoid exposure to asbestos

18.4 Problems in special cases

FOREWORD

The European Conference on Asbestos Hazards, held in Dresden in 2003 and attended by representatives from many European countries, the EU Commission and the ILO, drew attention to the fact that asbestos is still the most significant carcinogenic toxic substance in the workplace in most countries. With an estimated 20,000 deaths due to lung cancer and 10,000 cases of mesothelioma annually in industrialised countries in Western Europe, North America and Japan, it is clear that exposure to asbestos is still a major health problem that needs to be put back on the agenda and given top priority in our prevention activities. Asbestos remains central to all measures to safeguard workers' health.

According to European legislation, the marketing and use of products or substances containing asbestos were banned from January 2005 (Directive 1999/77/EC). Even stricter measures to protect workers from the risk of exposure to asbestos fibres have been in force since 15 April 2006 (Directive 2003/18/EC, which complements Directive 83/477/EEC). However, despite this legal framework, in practice the problem of how to prevent exposure to asbestos during removal, demolition, maintenance or servicing activities remains. In addition, in today's era of close economic ties and globalisation, we must be careful not to counteract our efforts by re-importing materials containing asbestos.

In line with the recommendations of the Dresden Declaration, the Senior Labour Inspectors Committee (SLIC) has formed a working group to produce practical guidance on best practice for activities involving the risk of exposure to asbestos and to conduct a European campaign in 2006 to monitor the implementation of the relevant directives.

The "Guide to Optimal Procedures

- Helps to identify and raise awareness of the presence of asbestos and asbestos products in the use, maintenance and repair of plant, equipment and buildings.

- Describes best practices for removing asbestos (including dust suppression, dust containment and protective equipment) and handling asbestos-cement products and wastes

- Supports an approach to protective equipment and clothing that takes into account human factors and individual differences.

It will be available to employers and employees.

The labour inspection campaign will be carried out in the second half of 2006 in all Member States of the European Union to protect the health of workers in all work involving the maintenance, demolition, removal or disposal of materials containing asbestos. The inspections will be carried out by national labour inspectorates (and health authorities if they are competent). The aim of the campaign is to support the implementation of Directive 2003/18/EC (which supplements Directive 83/477/EEC), which should be implemented by all Member States of the European Union by 15 April 2006 at the latest. The inspection campaign is preceded by information and briefing activities.

For our partners outside Europe, the labour inspectorates of the EU Member States offer their support. Existing SLIC training materials, 2006 campaign materials and best practice guides can be used in any other country where there is a willingness to address the health risks associated with asbestos and its use. For this, ILO Convention 162 can serve as a minimum standard. This convention and the examples of best practice represent the minimum level below which the international community should not fall.

Dear Reader, Dear Reader,

this "practical guide to best practice in preventing or minimising asbestos-related risks in work involving (or likely to involve) asbestos" is the result of joint collaboration between the Senior Labour Inspectors Committee (SLIC) and employers' and workers' representatives on the EU Committee's Advisory Committee on Safety and Health and represents a further step away from asbestos in European workplaces. We hope you will read this guide and keep it handy.

The main target groups are employers, workers and labour inspectors.

- For employers, the guide provides information on the latest technical, organisational and personal health and safety measures that they are obliged to apply.

- For the worker, the guide provides information on protective measures, focusing on the key issues for which

the worker should be trained, and motivates to actively contribute to safe and non-harmful working conditions.

contribute. - For the labour inspector, the guide describes the key aspects that should be examined during the inspection visit.

The guide is made available through a special website of the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work where you will find additional information and specific links to national health and safety websites related to the risk of exposure to asbestos.

Beyond its use in the 2006 asbestos inspection campaign, the guide aims to be a useful tool for all stakeholders in the field of work-related

asbestos exposure to create a common European basis with regard to best practices.

Dr Bernhard Brückner | Mr Jose-Ramon Biosca de Sagastuy Head of Institution Head of Institution DG Labour, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities Health, Safety and Hygiene at Work Luxembourg |

1. INTRODUCTION

This guide was produced by the Senior Labour Inspectors Committee (SLIC) in collaboration with the Advisory Committee on Safety and Health (ACSH) of the social partners (trade union and employer representatives) with the aim of providing labour inspectors, employers and workers across Europe with a common source of information accessible to all. Developed in support of the 2006 asbestos campaign, the guide should continue to be useful thereafter. It should therefore evolve with future advances in best practice.

The scope of this guide is ambitious in that information is presented on three scenarios:

- Work where asbestos may be involved (e.g. in buildings where there is a risk of asbestos being found unexpectedly due to incomplete documentation or incomplete removal).

- Work where low exposure to asbestos dust is expected

- Work involving a greater risk of exposure to asbestos dust and carried out by specialist companies

Therefore, the guide includes several chapters relevant to all three scenarios, as well as some chapters specifically dedicated to each scenario.

- Chapters 1 to 4 provide background information These chapters describe what asbestos is, its effects on health, the materials that contain asbestos and where they are found.

- Chapters 5 to 7 describe the planning and preparatory work to be done before work is carried out, for example: the risk assessment; the preparation of written instructions (or the work plan); the process used to decide what work is to be carried out and whether it is to be treated as reportable; whether medical surveillance is required; the training that staff receive

- Chapters 8 to 12 describe the practical organisation for carrying out work where workers are or may be exposed to asbestos. Chapter 8 describes the equipment required, chapter 9 the general approach to controlling Chapter 10 describes codes of practice for maintenance work where there is a risk of exposure to asbestos, chapter 11 presents codes of practice for low-risk work and chapter 12 describes codes of practice for notifiable asbestos work on (e.g. removal of asbestos).

- Chapters 13 to 18 discuss specific aspects: demolition work (Chapter 13), the worker and the working environment (Chapter 14), waste management (Chapter 15), monitoring and measurements (Chapter 16), other persons with special functions, for example the client, architects and facility managers (Chapter 17), and asbestos in other situations, for example in vehicles and machinery (Chapter 18).

- Chapter 19 describes the medical surveillance

Working with asbestos may involve working at high heights, at high temperatures, and with confining and cumbersome protective equipment. As this guide focuses on the prevention of health hazards due to asbestos, it should be noted that other risks (e.g. falls from heights, perhaps due to a friable asbestos cement roof) should not be ignored.

In terms of technical rules and practices to control and minimise risks from asbestos exposure, some clear differences in approach can be noted between Member States. In general, each approach has certain advantages and disadvantages. This guide provides explanations and clarifications of the different methods that could be considered as "best practices" for the particular approach and situation.

The following criteria were used to select methods to be included in the guide :

- the method is reliable and has proven itself

- the procedure takes into account features of different action instructions and should therefore theoretically be the best procedure

- the procedure is the best procedure under the circumstances

- Advances in the state of the art

In preparing the guide, care has been taken to make it as concise and readable as possible and to avoid repetition. Therefore, there are some cross-references between different sections, for example, to explain the considerations in the selection and use of protective clothing only once.

In a concise guide covering a wide range of practical work, there may occasionally be omissions of detail. Such omissions should therefore not be misunderstood as a deliberate exclusion of other measures.

Directive 2003/18/EC (Protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to asbestos at work), which complements Directive 83/477/EEC, has been implemented in Member States through national legislation, which may well vary in practical detail. This guidance is intentionally presented as non-mandatory so that it can offer the best practical advice without specifying whether the best practice is a mandatory requirement under national legislation in the EU Member States. Annex 1 provides a list of the relevant national legislation that has been communicated by each Member State.

As this guide focuses on avoiding hazards from exposure to asbestos, it does not attempt to cover the requirements of Directive 92/57/EEC on health and safety requirements for temporary or mobile construction sites. For example, in addition to sanitary facilities for the decontamination of persons, there must be adequate recreation rooms, as with all work on temporary or mobile construction sites. If a health and safety plan is required under the Health and Safety Directive for temporary or mobile construction sites, it should provide safe

include codes of practice for working with asbestos and documentation on the asbestos present at the site (e.g. abatement certificate).

This guide contains guidance specifically aimed at the employer, the employee and the labour inspector. However, readers are likely to find the guidance aimed at others informative as well. A chapter has also been included specifically aimed at other groups of people involved in asbestos work, for example clients who contract for the removal of asbestos, or the people who occupy a building after asbestos has been removed, or health and safety advisers.

The guide aims to give practical advice on removing and reducing exposure to asbestos dust. The focus is on good and best practice for reducing exposure to asbestos.

2 ASBEST

Asbestos is the fibrous form of several naturally occurring minerals. The main forms are:

- Chrysotile (white asbestos)

- Crocidolite (blue asbestos)

- Amosite (brown asbestos)

- Actinolite

- Anthophylite

- Tremolit

The first three forms were the main forms of asbestos used in commerce. Although known by their colour, they cannot be reliably identified by their colour alone. Laboratory analysis is necessary for this.

Asbestos may be present in a number of products (see chapter 4). If the fibres can be released, there is danger from inhaling asbestos fibres in the air we breathe. The microscopic fibres can settle in the lungs, remain there for many years and cause disease many years, usually several decades later.

A weak bond of the asbestos fibres in the product or material due to the brittleness or condition of the product/material increases the risk of release of the fibres. However, if the fibres are firmly bound to a material that is not brittle, the release of the fibres is less likely. Procedural rules have been introduced in several EU Member States that give priority to the removal of asbestos-containing materials that are considered more hazardous.

All forms of asbestos have been classified as Class 1 carcinogens, meaning that they cause cancer in humans. The EU Directive 2003/18/EC (Protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to asbestos at work), which complements Directive 83/477/EEC, requires that the exposure of workers to for all types of asbestos 0.1 fibres/ml must not be exceeded. Exposure to all types of asbestos shall be reduced to a minimum and shall in any case be below the limit value.

Some Member States require that the type of asbestos be taken into account when deciding on the priority of a hazard. For example, epidemiological evidence indicates that for a given fibre concentration (measured by the standard method for workplaces), crocidolite is more hazardous than amosite, which in turn is more hazardous than chrysotile. However, this does not change the practical need to apply best practice to avoid exposure to asbestos.

This guide presents practical guidance on how to avoid or minimise exposure to asbestos.

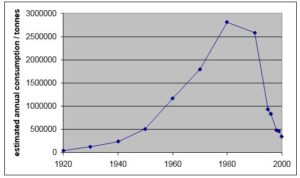

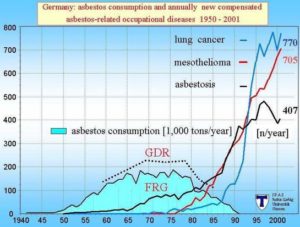

Annual asbestos consumption in Europe has changed considerably during the 20th century, as shown in Fig. 2.1. The data (for consumption in over 27 European countries according to Virta (2003)) clearly show that consumption increased sharply from about 1950 to about 1980 and then decreased as some Member States introduced restrictions on the use of asbestos or banned its use completely. The bans introduced by the European Directives in the 1990s accelerated the move away from asbestos. A comprehensive ban on the use and marketing of products containing asbestos (following EU Directive 1999/77/EC) came into force on 1 January 2005. The ban on the extraction of asbestos and the ban on the manufacture and processing of products containing asbestos (following Directive 2003/18/EC) came into force in April 2006. Consequently, the asbestos problems that continue to exist in Europe can be traced back to the asbestos present in buildings, installations or equipment.

There were also important differences between EU Member States. Some countries reduced asbestos use from around 1980, while others continued to use it until the end of the century.

Fig. 2.1 Estimated total consumption of asbestos in Europe from 1920 to 2000 (Data source: Virta (2003)

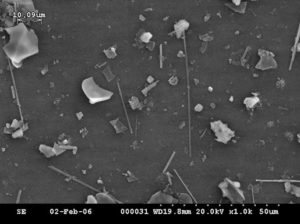

Fig. 2.2 Scanning electron micrograph shows chrysotile fibres

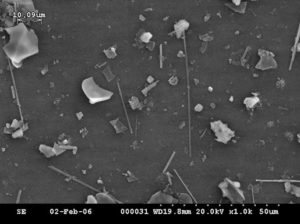

Fig. 2.3 Scanning electron micrograph shows amosite fibres

Asbestos is dangerous because the very fine fibres cannot be seen with the naked eye. Inhaling these fine asbestos fibres can lead to one of three diseases

- Asbestosis, a scarring of the lung tissue

- Lung cancer

- Mesothelioma, a cancer of the pleura (pleura: the slippery, thin skin that covers the lungs) or peritoneum (peritoneum: the slippery skin that lines the abdomen).

Asbestosis impedes breathing and can contribute to death. Lung cancer leads to death in about 95% of all cases. Lung cancer can also follow asbestosis. Mesothelioma is not curable and usually leads to death within 12 to 18 months of diagnosis.

Exposure to asbestos has been suspected to cause laryngeal cancer or gastrointestinal cancer. Oral ingestion of asbestos fibres (e.g. in contaminated drinking water) has been suspected as a cause of gastrointestinal cancer, and at least one study has shown an increased risk due to unusually high concentrations of asbestos fibres ingested via drinking water. However, these suspicions have not been (consistently) supported by the results of relevant studies.

Exposure to asbestos fibres can also lead to pleural plaques. These are discrete, fibrous or partially calcified, thickened areas on the surface of the pleura that can be detected on an X-ray or CT scan. Deposits on the pleura are not malignant and do not usually lead to limited lung function.

There are thousands of deaths in Europe each year due to asbestos-related diseases. At a conference on asbestos in 2003 (held at the instigation of the EU's Senior Labour Inspectors Committee (SLIC)), the likely number of deaths per year in a total of seven European countries (UK, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Norway, Poland, Estonia) was estimated at around 15,000

http://www.hvbg.de/e/asbest/konfrep/konfrep/repbeitr/takala_en.pdf .

At this conference, the relationship between asbestos use in Germany and the delayed occurrence of newly compensated asbestos-related diseases was described by Woitowitz with the graph shown in Fig. 2.1. Delayed occurrence means that new asbestos-related disease cases will continue to occur due to asbestos exposure during peak periods of asbestos use. Although the production of asbestos-containing products and materials has been phased out in the EU, there is still a risk of exposure to asbestos from the materials and products that are still in buildings, plant and equipment.

Fig. 3.1 Annual asbestos consumption and annual incidence of the disease in Germany (Source: Woitowitz (2003)

http://www.hvbg.de/e/asbest/konfrep/konfrep/repbeitr/woitowitz_en.pdf

In the UK, there were around 1900 deaths due to mesothelioma in 2001, 2002 and 2003 and it is expected that the incidence of mesothelioma will peak between 2011 and 2015 at between 2000 and 2400 deaths per year.

http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/tables/meso01.htm

It is estimated that deaths from lung cancer due to asbestos exposure are about twice as high as deaths from mesothelioma. Thus, the total annual number of deaths from asbestos-related cancer in the UK alone is currently estimated at around 5500 to 6000.

In countries where awareness of asbestos hazards is not yet as high, cancer diagnoses and statistics (especially for mesothelioma, which is difficult to diagnose) may be less reliable.

These diseases usually develop over longer periods of time and usually occur at the earliest 10-60 years after the first exposure to asbestos. The average latency period from first exposure is about 35-40 years for mesothelioma. The average latency period for lung cancer has been estimated to be about 20-40 years. There is no direct experience of adverse effects from inhalation of asbestos fibres.

Asbestosis usually develops due to years of high exposure to asbestos, and the disease usually occurs more than a decade after the initial exposure. The cases of asbestosis that continue to be reported in Western Europe were almost certainly caused by high exposure decades ago.

The risk of developing asbestos-related lung cancer and mesothelioma increases with exposure. The risk of disease is lower if asbestos exposure is kept as low as possible. However, there is no known threshold below which there is absolutely no risk of developing these cancers. Therefore, the use Optimum process important to eliminate or minimise the risk of exposure.

The risk of developing mesothelioma is estimated to be greater for those exposed to asbestos fibres at a younger age than for those exposed later.

It is generally accepted that lung cancer is much more common in smokers than in non-smokers. The risk of developing lung cancer due to exposure to asbestos is also greater in smokers than in non-smokers.

If you employ people who may be exposed to asbestos in their work, you should:

- Follow best practices (as outlined in this guide);

- ensure that people have been adequately trained and informed about the risks

- ensure that communication is effective (for example, not affected by communication difficulties);

- ensure that people understand the importance of minimising exposure;

- Provide information on the increased risks due to the combination of smoking and exposure to asbestos to encourage smokers to quit;

- comply with legislation relating to work where exposure to asbestos is possible.

If you may be exposed to asbestos in your work, you should:

- be aware of the risks due to exposure to asbestos;

- understand that it is important to keep exposure as low as possible;

- consider quitting smoking;

- Follow best practice when working with asbestos, as described in this guide.

If you are a labour inspector, you should:

- determine whether information (posters, brochures, etc.) on the health hazards associated with asbestos exposure is available;

- Check whether workers have been adequately informed about the increased risk for smokers exposed to asbestos, e.g. by looking for brochures or posters and by asking people concerned;

- Check whether the legal provisions on these matters have been complied with.

4.1 INTRODUCTION

Asbestos was widely used in many applications, for example for reinforcement or as a thermal, electrical or acoustic insulation material. It has been used in products subject to friction, in gaskets and adhesives. Its chemical resistance has led to its use in some processes, for example filtration or electrolytic processes. It has been used in commercial, industrial buildings as well as private homes, as illustrated in Figure 4.1. It is also found in the insulation material in railway carriages, ships and other vehicles, including aircraft and some military vehicles.

The extent to which a material releases asbestos fibres depends on whether the material is intact or damaged. The condition of asbestos-containing materials can change over time, for example due to damage, wear or ageing.

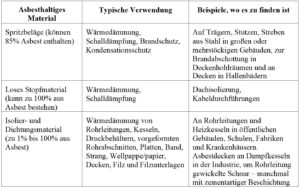

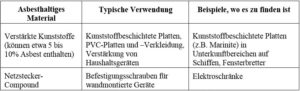

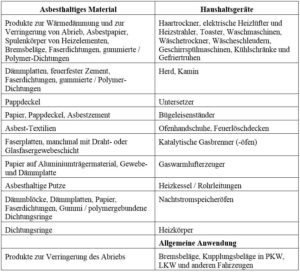

There are significant differences in the brittleness of different materials and the ease with which fibres can be released. Table 4.1 summarises examples of asbestos-containing materials and their typical use. The asbestos-containing materials are listed according to their potential for releasing asbestos fibres. Materials that are likely to release asbestos fibres readily are listed at the top of the list. There are some asbestos-containing materials (bituminous mixtures and rubber or plastic floor coverings) that are flammable. These flammable materials must not be not be disposed of by incineration because this would release asbestos fibres.

Table 4.1 Examples of materials containing asbestos with indication of the asbestos content

The extent to which the different types of asbestos-containing material have been used varies considerably between Member States. In some, asbestos was mainly used as asbestos cement. In other Member States (e.g. the UK), the use of structural coatings (a coating only a few millimetres thick containing about 5% of asbestos) was only popular at times.

Table 4.2 summarises examples of the use of some of these asbestos-containing materials in household appliances and industrial applications

Table 4.2 Examples of asbestos-containing materials and products used in household appliances and other applications

Products containing asbestos were manufactured by different manufacturers and offered under different trade names. In many cases, products that contained asbestos in the past were subsequently manufactured without asbestos. A comprehensive list of details of trade names, manufacturers and the periods when the manufactured product contained asbestos is available on the INRS website for products sold in France (INRS ED1475,

http://www.inrs.fr/inrs-pub/inrs01.nsf/B20B5BF9E88608EDC1256CD900519F98/$File/ed14 75.pdf ).

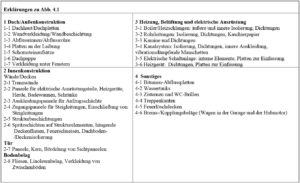

Fig. 4.1 The asbestos building shows typical places where asbestos-containing materials can be found.

4.2 WHAT YOU SHOULD DO

There is a possibility of exposure to asbestos when carrying out general maintenance or repair work in buildings. If you are involved in such work in these areas, the guidance provided here will be relevant to you:

If you employ or supervise people who may be exposed to asbestos-containing materials in the course of their work (see materials described above), you should:

- provide adequate training so that these persons recognise materials that may contain asbestos and know what to do and when to do it if they come into contact with materials that may contain asbestos;

- obtain good, reliable information on the presence or absence of asbestos-containing materials, for example from building plans and/or from architects, (in some Member States the responsible person must draw up a list of the asbestos-containing materials in a building);

- ensure that records are kept of the materials that are proven to be free of asbestos (for example, by your organisation or the owner of the building);

- provide written information on the presence of known asbestos-containing materials on site, including an asbestos inventory and, if appropriate, appropriate warning signs;

- provide written instructions on procedures to be followed if asbestos-containing materials are unexpectedly encountered (according to the information given in chapters 9 and 10).

If your work could release asbestos dust from a material listed above, you should:

- have received information before starting work as to whether or not these building materials contain asbestos;

- know how to recognise the products that might contain asbestos;

- know what to do if you come across materials containing asbestos (see chapters 5 to 10).

If you are a labour inspector, you should:

- check that workers carrying out maintenance work have been adequately trained to recognise materials that may contain asbestos;

- check whether sufficient information is available on materials that do or do not contain asbestos;

- check whether organisational arrangements are in place to ensure laboratory analysis of material samples that may contain asbestos;

- check whether there is a responsible person who can order the immediate interruption of work if materials are found that could contain asbestos;

- check whether the relevant national legislation has been complied with.

Fig. 4.2 Enclosure with asbestos insulation board (partially removed to show the asbestos cement flue pipe behind).

Fig. 4.3 Asbestos insulation board as partition wall. This example shows the practical problems of constructing a suitable seal and the areas where asbestos dust could accumulate during removal.

Fig. 4.4 Hole in the wall reveals asbestos pipe insulation

Fig. 4.5 An asbestos cement flue pipe sealed with asbestos cord is passed through a filler element made of asbestos

Fig. 4.6 Floor tiles containing asbestos

Fig. 4.7 Roofing felt containing asbestos

Fig. 4.8 Asbestos insulation on steam pipes

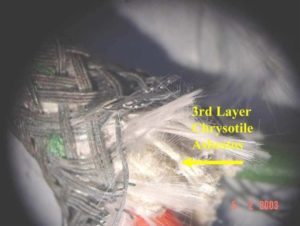

Fig. 4.9 Insulated cables with a layer of asbestos in the insulation

Fig. 4.10 Asbestos cement cladding at a factory

Fig. 4.11 Asbestos insulation on steel beams

Fig. 4.12 Sealing a chimney door with asbestos cord. On the right, a close-up of the asbestos cord.

5 RISK ASSESSMENT AND WORK PLAN BEFORE CARRYING OUT WORK

5.1 INTRODUCTION

When preparing a risk assessment and a work plan, the written documentation of the assessment and the information used for it is state of good practice.

In order to obtain information about where asbestos is located, an investigation by competent professionals may be required. The procedures for carrying out such investigations are not covered in this guide, but it is important that the responsible person (employer, manager, worker) knows that they are required. The information should be provided in a form that is easy to understand.

Where this information is available, it is important that any limitations indicated in the information are observed. For example, it is possible that not all cavities in the walls were tested during an investigation.

In some Member States, there may be a principle that asbestos (especially weakly bonded asbestos) should be removed whenever possible. In that case, a finding that asbestos is present may result in the need to comply with legislation requiring safe removal.

In other Member States, the decision on what to do with the asbestos-containing material is based on an examination of the factors relating to the risk of release of asbestos fibres from the material. This decision-making process is described in Section 6.2. Subject to this decision, asbestos-containing materials can remain where they are and be treated as a hazard that is safe as long as the materials are well maintained, well sealed, recorded in writing (e.g. on the building plans) and appropriately labelled.

Asbestos that is not removed must be inspected regularly to ensure that the material remains in good condition. In addition, it shall be clarified that the organisation and control of nearby works are effective. If the asbestos is not in good condition or cannot be maintained in a safe condition, removal shall be organised.

When a decision has been made that work is to be carried out where asbestos-containing materials are encountered or asbestos dust is released, a written assessment of the hazard and the consequential risks must be prepared. The risk assessment should be site-specific, i.e. include the specifics of the site, and should include an assessment of the potential exposures and a summary of the available experience in controlling exposure to asbestos in similar circumstances. The risk assessment should consider the risks of asbestos exposure to workers as well as to other involved persons in the vicinity (e.g. residents). This may be based on measurements of similar or previous work. Typical exposure concentrations as measured by the UK Health and Safety Executive in work involving asbestos cladding, coating and asbestos insulation board are given in Annex 1.

Written instructions (sometimes called a "written work plan") shall be prepared for each work task.

The conditions under which work with asbestos is carried out create certain practical difficulties in relation to emergencies, such as sudden incapacitating illness or injury. Access may be restricted (especially if the work is carried out in an enclosure, see Chapter 12) and the wearing of respiratory equipment impedes communication. Emergency procedures must cover accidents and illnesses within an enclosure. This requires the following information:

- Number and names of first aiders

- Identification of first responders (when all persons are wearing protective clothing and full respiratory equipment covering the face).

- Organisation of communication between people inside and people outside the enclosure (especially in emergencies).

- Quick access points in emergencies to an enclosure, and when and how to use them.

- Rules of procedure for the access of rescue personnel

- Location of emergency exits and emergency equipment

- Detailed decontamination procedures to be followed after a hasty emergency access (e.g. access to help an injured, immobilised worker in the enclosure).

The emergency procedures should also specify what measures are to be taken in the event of an emergency evacuation of the building or site (e.g. following a fire or bomb alarm) of workers in personal protective equipment that may be contaminated with asbestos.

The written risk assessments and instructions (work plan) should be freely available at the construction site. They should take into account foreseeable emergencies and indicate procedural rules to be followed and the persons responsible in such an event.

5.2 WHAT YOU MUST DO

If you employ or supervise people who are likely to release asbestos dust in the course of their work, you must:

- have prepared a written risk assessment and a written work plan for each task;

- ensure that the risk assessment takes into account the characteristics of the particular worksite and the activities and includes a sufficient basis for estimating the potential exposure;

- ensure that the risk assessment takes into account the exposure of all persons concerned (for example, machine operators, residents, contractor employees, etc.);

- ensure that the plan is detailed and relates to the particular site and the work carried out there;

- Include preparatory work in the plan (e.g. erecting an enclosure);

- include a clear diagram of the site in the plan showing the location of the equipment (e.g. enclosure, airlocks, decontamination unit, negative pressure units, waste material passageway, secure contaminant container);

- consult workers who have practical knowledge to ensure that the risk assessment and work plan are realistic;

- ensure that copies of the risk assessment and the work plan are available on site and are available to those involved in carrying out the work;

- ensure that the risk assessment and the work plan are explained to the workforce and to the persons affected by the work;

- ensure that copies of the risk assessment and the work plan have been sent to the supervisory authorities if required by national legislation;

- Include rules of procedure for behaviour in emergency situations (including those in section 5.1 situations described).

If you are about to carry out work that may release asbestos dust, you should:

- be consulted in the risk assessment and in the work plan;

- Offer your suggestions on practical problems concerning the work plan and risk assessment;

- have a copy of the risk assessment and the work plan;ensure that you have the work plan

- Ensure that you follow the work plan

If you are a labour inspector, you should check whether:

- an adequate and appropriate risk assessment is available at the construction site with regard to the exposure of workers as well as other persons;

- written instructions (work plan) with specific site details are available at the construction site;

- there is an emergency plan (e.g. as part of the work plan);

- workers have an adequate understanding of the risk assessment and the work plan;

- the risk assessment and work plan show that workers' comments have been taken into account.

5.3 TEMPLATE FOR A WORK PLAN CHECKLIST

The national regulatory body may provide guidance on the design of work plans (e.g. the "Method statement aide memoire" http://www.hse.gov.uk/aboutus/meetings/alg/policy/02-03.pdf ). A work plan may contain cross-references to general information on working methods to be included. The work plan should always be comprehensive and describe all site and task specific features (e.g. plan of the construction site as well as any deviations from the generally accepted methods).

The following checklist for a work plan is based on guidance in INRS, 1998 ED 815, Appendix 6 and the "Method statement aide memoire"of the UK Health and Safety Executive.

This example is a non-exhaustive list of items that the work plan should include or consider. It should also include the items for reportable work (see Chapter 12). For low-risk work (see chapter 11), the work plan can be less comprehensive, but should include the sections or items marked with an asterisk (*).

*Front page

Under the logo of the organisation carrying out the work:

- Release date

- General title of the project (removal of asbestos, encapsulation )

- Type of material containing asbestos

- national licences or permits to carry out the work (if required by national legislation), date and duration of the work

- Name of the person responsible for the work and the name of the client

- exact address of the construction site

- Name of doctor (in EU Member States where a doctor is involved in occupational health and safety)

- Planned date of arrival of the executing company at the construction site

Administrative information

- Contractor or organisation carrying out the work on the asbestos-containing materials (name of director, representative on site; with addresses, telephone and fax numbers).

- Persons responsible for the work (telephone and fax numbers)

- Name of the appointed consultant present on the construction site

- the laboratory commissioned to carry out the measurements on the construction site (address, telephone and fax number)

- Subcontractors, in particular for preparatory work

- List of officially participating organisations

* Information about the construction site

- * Location (e.g. shop in a shopping centre)

- * Type of work

- Planned treatment, removal and/or encapsulation

- Asbestos type (crocidolite, chrysotile )

- Type and condition of the asbestos-containing materials, quantity and distribution on the construction site

- * Work programme, including date and time of the work

- Staff

- daily routine programme

- Designated areas

- Markings (type of signs, number, locations)

- Pathway for pollutant disposal

- Location of the decontamination unit

- Sanitary facilities and recreation rooms

- factors specific to the location (proximity to other activities, work in high temperatures, air conditioning or heating systems, work at height ).

Factors affecting the plan for removal or encapsulation

- Analysis of the risks from asbestos and other factors related either to the workplace (e.g. electricity, gas, steam, fire, machinery, working at height) or to the materials and equipment used.

- Measurement of fibre concentrations (or asbestos fibre concentrations) before the procedure

- the likely exposure to asbestos during removal or encapsulation

Setting up the work (enclosure etc.) on the construction site

- Facilities for staff (drinks, sanitary facilities)

- Separation and marking of the area

- Effects on other activities in the building or the surrounding area

Preparatory work

- Removal of equipment and materials

- Establishment of a supply network and drainage (electricity, water, ventilation)

- Adaptation of building installations in the working area (fire alarm, electricity, gas, central heating, air conditioning, etc.)

- Materials and equipment required for the work

Preparation of the area where asbestos work will take place

- Separation and enclosure (see chapter 12)

- Generation of negative pressure

- Pre-cleaning of the work area and the installation objects, removal or covering of installation objects.

- Enclosure of the area (safe working methods, materials and emergency exits)

- Negative pressure and air extraction

- Smoke tests, process and criteria for acceptance

Removal or encapsulation of asbestos

- Methods (injection, spraying, manual scraping etc.), equipment (injection equipment, spraying equipment) and materials (wetting agents, cleaning agents )

- Protection of workers (respirator)

- Quality control procedures (working methods and effectiveness of treatment)

Control programmes (monitoring and measurements)

- Sampling plan for the period of the work (see chapter 16)

- Systems for monitoring and controlling the effectiveness of the enclosure

- Plan of the locations where sampling is foreseen

Removal of waste materials

- Condition of waste materials (asbestos as well as non-asbestos containing material), handling procedures

- Waste disposal, safe storage on site and procedures for disposal to approved landfill sites.

Cleaning the work area

- Procedure for removing the surface material and cleaning the surfaces

- Methods for decontamination of materials and equipment used in the work

- Visual inspection and cleanliness check. System for maintaining negative pressure. Appointed person is responsible for the control systems.

After completion of the remediation work, the restoration of the area for normal use

- Sampling to test the indoor air for asbestos dust, sampling plan, laboratory takes over the work

- Finally, removal of the equipment from the area

Description and characteristics of the materials and equipment used in the course of the work

- Equipment for personnel (including type of breathing apparatus)

- Decontamination unit (and documentation of test methods confirming that it is not contaminated due to previous operations).

- Enclosure and associated equipment

- Size of the enclosure

- Negative pressure units (number and capacity, air exchange rate)

- Air lock, bag lock

- Water heater, water filter

- Lighting

- Injection equipment and other dust-binding equipment

- Emergency equipment

- Consumables (filters, ).

Emergency measures

- First aiders, emergency measures for situations with varying degrees of urgency and danger

- Procedures established for assistance in emergencies

- Communication (to call for help from inside the enclosure)

- Coordination with external emergency services

Plans and diagrams of the construction site

- Location of the construction site/enclosure in relation to other activities and enterprises

- The enclosure, its size and shape and the location of:

- Viewing panels and monitoring television (if required)

- Negative pressure units and associated air exchange points

- Industrial hoover of the class (for asbestos)

- Bag lock, waste passageway, safe waste storage (e.g. tipper)

- Location of the decontamination unit, passageways (if there is no direct connection between the decontamination unit and the enclosure) and airlock access to the enclosure.

- Arrangement of networks and facilities involved in the work (e.g. air intake points, water and power supply for the decontamination unit).

- Positioning of the connection points, if A network of compressed air supply connection points is used to supply the respiratory protective devices.

6 DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

6.1 NECESSARY DECISIONS

This chapter describes the logical decision-making process when it comes to:

- Determine whether it is better to leave the asbestos-containing materials in place (while adequately securing them and adequately controlling and managing them) or to remove the asbestos.

- to decide whether certain maintenance work can be carried out in such a way that there is only a low risk of exposure to asbestos and can be classified as work with "occasional exposure of low level" which can be carried out without prior notification to the competent authority.

6.2 GUIDANCE ON DECISIONS ON ASBESTOS-CONTAINING MATERIALS IN BUILDINGS

A number of key decisions need to be made before carrying out work where asbestos-containing materials may be involved. These decisions are closely linked to the hazard assessment and planning process (chapter 5). The risk assessments will determine which decisions are appropriate; these decisions will affect the purpose and content of the plans to be developed.

Several factors need to be taken into account when deciding on the work that may be required. In some Member States of the European Union, there is national legislation which in principle requires the removal of asbestos-containing materials (particularly materials containing weakly bound fibres) where it is practicable to do so. Other Member States make the decision as to whether to remove asbestos-containing materials on the spot The decision as to whether or not materials can be left in place depends on certain criteria, such as condition, location, access and thus the overall likelihood of the material potentially posing a risk from the release of asbestos fines. National legislation must therefore be taken into account when deciding whether materials should be secured (e.g. by encapsulation and/or containment) and can be left in place.

Subject to national legislation, materials containing asbestos which are in a safe condition (i.e. undamaged, enclosed or encapsulated) may be left in situ provided that effective monitoring and management of the secured material is ensured. If material containing asbestos is left in place, it must be identified in the building's documentation and plans so that its presence is taken into account in future works. In addition, a system should be in place to monitor the asbestos-containing material and manage its condition (e.g. keep material in good condition).

Fig. 6.1 and 6.2 show logical decision trees. The starting point is to identify whether a material is asbestos or not. This is followed by a system to arrive at the decision whether the material should be removed or not. Once it is known that the material contains asbestos, a series of questions follows as to whether the asbestos-containing material.

- is in good condition; or

- can only be repaired with difficulty

- accessible (in which case it may be damaged accidentally or intentionally; if it is not accessible, removal may be hindered and limited).

- is damaged, with more than minor and superficial damage (so that repair would be unreliable)

- is extensively damaged (i.e. widespread damage so that encapsulation of the damaged parts is no longer feasible)

- cannot be encapsulated or enclosed (for reasons other than those mentioned)

If the asbestos-containing material is not in good condition, cannot be easily repaired, is easily accessible (and therefore potentially subject to further damage or disturbance), is extensively damaged, and if there is no practical way to encapsulate or contain the material, then the material must be removed. This decision applies to any type of asbestos-containing material.

The alternative to removing the asbestos-containing materials is to make the materials safe (by keeping them in good condition or enclosing them) and to monitor and manage them on site.

Even if asbestos-containing material can be made safe and monitored and managed in place, it is necessary to consider the possible requirements of usual renovation work in the building. If the materials interfere with the usual renovation work in the building, removing the asbestos-containing material would be the right decision.

For asbestos cement and other materials with tightly bound fibres, the decision-making process would likely result in a decision to leave the material in place, document, monitor and manage it.

Fig. 6.1 Decision tree for materials suspected of containing asbestos

6.3 DECISIONS REGARDING THE NOTIFIABILITY OF WORK

The risk assessment is the basis for deciding whether work should be treated as notifiable asbestos work.

Directive 2003/18/EC (Protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to asbestos at work), which supplements Directive 83/477/EEC, applies to all workers who may be exposed to dust from materials containing asbestos.

The European Directive 2003/18/EC requires that the work must be reported (to the supervisory authority in the respective EU member state) and that health surveillance of workers must be carried out and documented in writing. In addition, it requires that employers report on workers "keep a register indicating the nature and duration of their activities and the hazards to which they have been exposed." In certain clearly defined cases, these provisions need not be applied. "Provided that the exposures are occasional and of low level and that it is clear from the results of the risk assessment that the exposure limit value for asbestos in the air in the working area is not exceeded, it is not necessary to [above regulations] not to be applied to the following operations:

- Short, non-consecutive maintenance work, working only on non-friable materials.

- Removal of intact materials in which the asbestos fibres are firmly bound in a matrix, whereby these materials are not damaged

- Encapsulation and wrapping of asbestos-containing materials in good condition

- Air monitoring and control and sampling to determine the presence of asbestos in a particular "

A process for deciding whether works meet the criteria for non-application of the legislation is illustrated in Fig. 6.3.

The Directive (2003/18/EC) defines the exposure limit for asbestos as 0.1 fibres/cm3(weighted average over 8 hours). Some Member States of the European Union determine the time average over shorter periods (4 hours or 1 hour).

The national regulations of the Member States may differ as to whether and to what extent use is made of the possibility of waiving these provisions.

Therefore, all work with friable materials (e.g. sprayed coverings, cladding, loose tamping material) must be treated as notifiable and also require medical supervision. In the case of other materials, the condition must be assessed and a risk assessment carried out in order to obtain the necessary information for a decision on a possible exemption in relation to the reporting obligation.

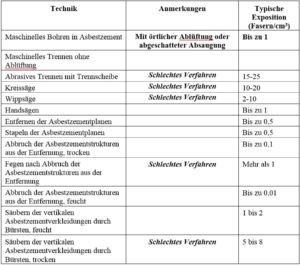

For work involving the handling of materials with firmly bound fibres, e.g. asbestos cement, the risk assessment must take into account the nature and duration of the work. Annex 1 gives examples of air concentrations that have been reported as typical for various activities involving asbestos cement.

If you employ or supervise people who are likely to be exposed to asbestos dust in the course of their work, you should:

- carry out the risk assessment for the respective work;

- use the decision-making process to determine the appropriate course of action (i.e. decide whether the material can be removed or secured and left in place and managed, and whether the work is reportable);

- prepare and maintain written records of the type of material (e.g. sprayed coating or insulation board or asbestos cement) and its condition (e.g. comment on the type and position of damage, using photographs if possible);

- prepare documentation on the documents used in the risk assessment to estimate the possible air concentration;

- Record the decision-making process (e.g. the answers to the questions in the relevant logical decision trees);

- plan the work as well as organise indoor air measurements, unless there is clear evidence of the air concentrations that are likely to be expected

If asbestos-containing material is likely to be damaged during your work, you should:

- be involved in the risk assessment that contributes to the above decision-making process.

If you are a supervisor and inspect a construction site where there are materials containing asbestos, you should:

- examine the evidence that the decision not to remove the material was justified;

- check whether the condition of the materials that led to an assessment of the work as non-notifiable in the risk assessment does in fact meet the criteria described in section 6.3 (e.g. not brittle, not degraded, in good condition);

- check that monitoring and management of materials left on site are ensured;

- consider whether the information is adequate for estimating likely exposures, especially if the risk assessment indicated a low level exposure.

Fig. 6.3 Decision tree to decide whether the work is notifiable

Fig. 6.4 Insulating panel containing asbestos. Removal of the panel should be considered as the panel could easily be damaged at this point.

7 INSTRUCTION AND INFORMATION

7.1 INTRODUCTION

This chapter outlines the topics to be covered in a training programme and refers to other publications that give further details. In particular, the report by Bard et al (2001), which sets out detailed recommendations on the structure and content of an asbestos training programme, provides detailed information to training providers. The European Directive (2003/18/EC) states: "Employers shall provide adequate training for all workers who are or may be exposed to dust containing asbestos. This training shall be provided at regular intervals and shall be free of charge for workers. 2. The content of the training shall be easily understood by workers. The training must provide workers with the knowledge and competence necessary for prevention and safety ..."

The recommendations of a SLIC working group are described in: http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/safework/labinsp/asbestos_conf/inforen.pdf. Training recommendations from the UK are described at: http://www.hse.gov.uk/aboutus/meetings/alg/licence/04-04.pdf.

The training should be presented in a way that is easily understood by the participants (employer, supervisor or worker) and include practical exercises on the use of all equipment. It must be given in the language that workers (especially workers of other nationalities) know and understand.

This chapter also includes a brief guide to the required training programme (initial training, refresher courses, regular review of training needs, etc.). Finally, some suggestions are given for supporting information material to consolidate the training success.

This chapter aims to make it clear to the employer what training he must organise for workers, supervisors and himself. The worker should know what training he is entitled to. This information also serves to provide the labour inspector with a clearly described framework for checking the adequacy and effectiveness of the training.

7.2 CONTENT OF THE TRAINING

7.2.1 Essential training content for all work involving asbestos

Training for all persons (employer, supervisor, worker) involved in work where they may (eventually) be exposed to asbestos-containing material should include the following topics:

- Properties of asbestos and its health effects, including the synergistic effect of smoking

- different types of materials and products that may contain asbestos and where they are likely to be found

- Importance of the condition of the material/products for the possibility of asbestos fibres being released

- necessary measures when encountering materials that may contain asbestos.

7.2.2 Essential training content for general construction work

Workers, employers and supervisory staff who may be exposed to asbestos in the workplace shall receive appropriate training. This training shall cover the following in addition to the content listed in section 7.2.1:

- The type and extent of information that should be available where asbestos-containing materials are located (e.g. some EU Member States require inventories on the occurrence and location of asbestos-containing materials in buildings).

- The obligation to stop work immediately if materials are found that are suspected to contain asbestos and to inform the responsible supervisor.

- measures required to reduce potential exposure should the suspected asbestos-containing material be in poor condition or accidentally damaged (e.g. clearing the immediate area, necessary safety measures and informing the responsible supervisor

- for the supervisor and the employer as addressees: laboratory analytical sample testing to confirm the presence or absence of asbestos.

The training should also address emergency situations where the suspicion of asbestos in a material arises after it has been damaged. In this case, the training should provide procedures to ensure that the situation is not made worse by inappropriate actions (e.g. trying to sweep up the material) or by inaction that will perpetuate exposure to asbestos.

7.2.3 Essential training content for low-risk asbestos work

If the training is intended for workers performing low-risk work, i.e. work that meets the criteria set out in section 6.3, it shall cover the content specified in section 7.2.1 and beyond:

- Activities that could lead to exposure to asbestos

- Importance of effective control measures to prevent or minimise exposure to asbestos dust and to prevent the spread of asbestos contamination

- safe work practices that minimise exposure, including control techniques, personal protective equipment, risk assessments and written instructions (work plan)

- Importance of respiratory protective equipment, selection of the appropriate respirator and its proper use

- appropriate care and maintenance of personal protective equipment and respiratory protective equipment

- Procedure for the decontamination of persons

- Procedures for the following emergency situations, B.: accidental damage to asbestos-containing materials or injury or illness to persons during the performance of asbestos work.

- Waste disposal, appropriate encapsulation (e.g. bagging or wrapping) of the waste material to prevent the spread of contamination, labelling and provision of a secure tipper or container at the point of transport by a licensed asbestos waste disposal contractor to an approved (or licensed) landfill.

For workers and supervisors, training shall include practical exercises to familiarise them with material samples and to practice the proper use and maintenance of equipment and appropriate working techniques.

Training of supervisors and employers should also include legal responsibilities and supervision of work.

7.2.4 Essential training content for work involving the removal of asbestos

If the training is for workers carrying out reportable work (i.e. the hazard assessed does not meet the criteria for low risk and limited scope work set out in section 6.3), then more comprehensive training is required. It should cover the topics listed in section 7.2.3, but in addition cover the nature of the work and topics relevant to reportable work.

The training of workers who remove asbestos must include practical exercises so that they learn how to use and maintain equipment related to safety (enclosures, personal protective equipment, respiratory protective equipment, decontamination units, dust suppression equipment and equipment for the controlled removal of asbestos-containing materials).

The topics listed in sections 7.2.1 and 7.2.3 shall be expanded to include the following:

- When discussing the health effects of asbestos, the relationship between exposure and risk of disease should be emphasised to highlight the importance of preventing or minimising exposure to asbestos.

- When discussing the products that may contain asbestos, detail the characteristics of the products that may need to be considered during removal

- The following should also be addressed when discussing safe work practices:

- Good work planning, including good site design (positioning of equipment, e.g. airlocks; decontamination unit; shortest, safest route to move waste to a safe tipper).

- Suitable and sufficient risk assessment covering all aspects of the work and a detailed work plan

- Preparation of the construction site before erecting an enclosure/partition, including any prior clean-up that may be required.

- Procedure of erecting a bulkhead, additional protection of the floor and all weak points. Ensure that all parts of the bulkhead can be adequately cleaned, i.e. there should be no places where dust/dirt can settle. Waste locks, air locks, vision panels (and monitoring TV if necessary), negative pressure units, including easily changed pre-filters, cables to supply power from outside the enclosure so that fuses etc. can be changed.

- Maintenance of an enclosure (effectiveness of ventilation - negative pressure unit, integrity of enclosure, periodic inspections, etc.), including importance of smoke tests before starting work.

- Techniques for removing asbestos with minimal dust release, including dust suppression methods such as 'wet stripping' , prompt bagging of material to prevent the spread of dust (on feet, equipment or clothing) and, for supervising personnel, monitoring the effectiveness of the

- Cleaning of the enclosure, airlocks and sanitary facilities; comprehensive cleaning (from top to bottom).

- Effective communication (also between the persons inside the enclosure and the persons outside the enclosure)

- Cleaning again if an enclosure is not released

- Process for cleaning and dismantling the

- When discussing respiratory protective equipment, the following should also be addressed:

- Positive pressure ventilation and/or compressed air bonnet

- Cleaning/maintenance of breathing apparatus

- The importance of checking the fit of equipment, and factors that influence this; inspection, testing, cleaning and maintenance of respiratory equipment

- Different types of breathing apparatus, their advantages and limitations

- Emergency measures in case the supply (power or compressed air) fails in a work situation

- Possible limitations (e.g. in visibility) and difficulties in using respiratory equipment.

- The emergency procedures training would cover procedures for the following situations:

- Assistance measures for people who are injured or become ill in an asbestos enclosure

- Evacuation in emergencies (e.g. fire)

- Power or equipment failure (negative pressure, breathing apparatus)

- Leak outside the enclosure

- Interruption of the water supply to the sanitary unit

- Training for procedures for decontamination of persons would include the following:

- The use of airlocks, entry/exit to the enclosure and decontamination unit, which may be either directly connected to the enclosure or separate from it.

- Change of personal protective equipment, showers, disposal of overalls

- Maintenance of a decontamination unit

- Decontamination of persons in the event of an accident or evacuation

- Correct use and maintenance of equipment used in the removal of asbestos

- Other potential hazards, e.g. removing asbestos at high temperatures, working at great heights, setting up and using access equipment for higher workplaces

- Waste disposal:

- Method for bagging and wrapping waste

- Secure containment (e.g. wrapping and/or bagging)

- Labelling

- Safe passage through bag lock and defined path from enclosure to safe storage location

- Transport of waste from the remediation site to an approved landfill by an approved asbestos waste disposal company.

- Proof of traceability of the waste from the construction site to the landfill (e.g. consignment note).

For workers who are required by the Directive to undergo medical examinations, the training should include the following:

- Health control requirements, including their purpose and importance (as described in chapter 19) and the need to have documents to prove that it has indeed taken place

- The information and advice that may be given to workers after a medical examination.

For supervisors and employers, training should also include the following:

- good planning

- Inspection and testing of equipment (e.g. decontamination unit, enclosure, dust suppression equipment ); how to detect defects.

- Inspection of the work during its execution

- Checking the effectiveness of fibre concentration monitoring

- Review of competence and training needs

- Record keeping

- Need to intensively train new workers

In addition to practical supervision, the training of supervisors and employers must take into account the principles outlined in chapter 5 and 6 topics covered, i.e.

- Drawing up a risk assessment (with regard to the exposure of workers and other persons) and a work plan

- Relevant laws and regulations

- their functions and responsibilities

For all persons involved in the removal of asbestos, the training should create an understanding of the air sampling and clearance tests that are carried out during and after the completion of the work (see chapter 16).

Fig. 7.1 Practical exercise in using an H-type hoover to remove simulated contaminated material (talcum powder). This illustration was provided by the UK HSE.

7.3 TRAINING PROGRAMME - YOUR TASK

If you employ or supervise people who may be exposed to asbestos in the course of their work, you should:

- Provide appropriate induction training, as outlined above, before these people take on the work;

- assess whether a refresher course is needed - it should be conducted at least once a year and when there are changes in procedures or the nature of the work - and keep appropriate records;

- regularly conduct task-specific briefings (so-called toolbox talks), especially if a particular task involves something unusual;

- Organise training by a competent provider (e.g. organisation or person with knowledge of proper procedures and good working practices and with skills in delivering training content);

- ensure that each course participant is instructed in a language they understand;

- Keep records of the successfully completed training course, which must be accessible to every person in the workplace;

- Proper supervision in the workplace with special attention to newly qualified workers

If your work involves a risk of exposure to asbestos, you should:

receive adequate training before taking over the work;

have the need for refresher courses assessed regularly (at least once a year) and whenever there is a significant change in the nature of the work;

Inform your employer if there are any language issues that might affect your understanding of the training (for example, does your employer know what your mother tongue is?).

If you are a labour inspector, you should:

- check that there is documentation of successfully completed training courses for each worker on the site;

- check whether there are records of periodic assessments of the need for refresher courses for individual workers;

- check that training of workers of foreign nationality has been provided in a language/languages they understand;

- check that the training has been provided by a competent training company or trainer.

7.4 INFORMATION

For all activities where workers are or may be exposed to dust from asbestos-containing materials, Directive 2003/18/EC (protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to asbestos at work), which complements Directive 83/477/EEC, requires that workers and their representatives receive adequate information on:

- the health risks due to exposure to asbestos dust or materials containing asbestos

- the legally binding limit values and the requirement to monitor the release of asbestos dust

- Hygiene requirements, including the need to refrain from smoking

- the precautions to be taken with regard to the wearing and use of protective equipment and clothing

- special precautions designed to minimise exposure to asbestos.

These points are included in the training programme recommended above. In addition, information on these issues should also be readily available in the workplace in an appropriate form (e.g. posters, notices or brochures).

8 EQUIPMENT

8.1 EQUIPMENT

Suitable equipment must be available for the work. Basic equipment for most tasks is listed in this section. The equipment must be kept in good condition and therefore as described in section 8.2 described above.

8.1.1 For low-risk work (not reportable)

For low hazard work with asbestos (which is not reportable), the required equipment includes the following:

- Materials for isolating and separating the work area (tapes, barriers, markings, warning signs)

- Materials to prevent the spread of contamination (durable 125 and 250 µm thick polyethylene film [also known as 500 and 1000 thickness polyethylene film], wood, plastic or metal materials).

- Smoke test tubes for checking the integrity of small enclosures

- Personal protective equipment (e.g. disposable overalls; washable boots) and respiratory protective equipment (e.g. disposable respirators suitable for asbestos EN 149 type FFP3 or EN405 half masks - with face fit test to determine suitability for individual workers and regular replacement of dirty filters).

- H-type hoover, i.e. a hoover with HEPA (High Efficiency Particulate Air) filters manufactured in accordance with the international specifications for use with asbestos.

- Dust suppression equipment, e.g. local exhaust with connection to H-type hoover for collecting dust from boreholes, etc.

- suitable asbestos waste containers (e.g. properly labelled plastic bags)

- Cleaning equipment and consumables (damp wipes, dust absorbing cloths, fine airless water spray).

- Safe storage of the waste

- Hygiene facilities for personal decontamination (washing facilities, preferably a shower), with storage facilities for work clothing and protective clothing separate from normal street clothing (see section 8.1.2 for personal decontamination facilities required for reportable work with asbestos).

- Consumables for personal decontamination (shower gel, nail brushes, towels)

- Equipment for water filtration

8.1.2 Additional equipment for reportable work

For notifiable work with asbestos, you also need the following:

- Full enclosure (durable polythene sheeting, frame and vacuum unit with pressure monitoring equipment; one EU Member State requires pressure monitoring equipment that continuously records readings).

- the enclosure should have clean viewing windows or television surveillance to allow the work and workers to be inspected without having to enter the enclosure

- Good lighting (mobile, cleanable lamps suitable for use in the enclosure).

- Smoke generator for checking the integrity of large enclosures

- High performance full facepiece respirators (with personnel who have conducted face fit tests for this type of respiratory equipment); or air-supplied respirator.

- personal protective equipment (disposable overalls and washable boots)

- fully cleanable decontamination unit, with adjustable heated shower and separate areas for clean clothing and for discarded and contaminated disposable workwear. There must be a certificate confirming that the decontamination unit has been tested and found not to be contaminated prior to its arrival on site. There must be at least one shower (decontamination unit) for every four workers engaged in the asbestos work.

- Filtration of the waste water prevents the spread of asbestos

- the best practice (used in some EU Member States) is to use a five-chamber unit with two shower rooms (see section 12.4 for a diagram showing the layout and proper use of decontamination equipment). This five-chamber system is used where workers wear waterproof sealed coveralls that are cleaned under a shower. After removing the showered washable coveralls, which can be stored in the middle chamber, the worker uses the next shower chamber. A widely used and accepted alternative is a three-stage unit consisting of a shower between a 'clean end' and a 'dirty end'; this system is suitable for workers wearing disposable coveralls.

- A high-efficiency-particulate-air (HEPA) filter exhaust provides airflow (through grilles) from the 'clean end' to the 'dirty end' of the decontamination unit. Self-closing doors provide separation of the sections. In cold seasons, the clean end should be heated to provide a comfortable warm environment for changing and showering.

- A negative pressure unit (exhaust fan with HEPA filter) to maintain ventilation inside the enclosures, with control unit to monitor pressure. The best practice (defined in an EU Member State) is to use continuously recording control devices (e.g. making a paper record of the pressure difference). One Member State requires that the negative pressure unit conforms to a national quality standard (British Standards Institution; PAS 60 Part 2).

- For notifiable work (chapter 12), in particular for the removal of materials containing only weakly bonded asbestos, an emergency generator is installed in a Member State of the European Union to supply the

key electrical equipment (negative pressure ventilation, lighting etc. in the enclosure) and sufficient storage tanks for water to ensure water supply for personal decontamination recommended. (The equipment may only be operated by appropriately trained and competent persons).

- Dust suppression equipment, for injecting water into asbestos-containing insulation prior to removal and for spraying surfaces of asbestos-containing materials.

- safe storage of the asbestos waste

This list is not exhaustive, but shows how much equipment is needed to be protected from the risk of asbestos exposure. Other equipment (such as fire extinguishers and first aid equipment) is also required.

8.1.3 Selection of respiratory protection equipment

The European Directive 2003/18/EC states that in the case of activities (such as repair, maintenance, removal and demolition work) which may give rise to asbestos concentrations in excess of the permissible exposure limit value (for the value see section 6.3), the employer must establish further measures to protect workers, in particular that "the workers shall obtain appropriate respiratory and other personal protective equipment to be worn". Therefore, based on the risk assessment (chapter 5) suitable respiratory protective equipment is selected. A guide to the selection, use and care of respiratory protective equipment can be found in EN 529.

The selection should be based on the following principles:

- the concentration inside the facepiece must be kept as low as possible, it must in no case exceed the exposure limit

- the equipment must be suitable for the worker and the conditions in which he/she works

- the nature of the work, B. the range of movement required, and any obstacles or restrictions

- the conditions at the construction site, e.g. possibility of access and free movement in the work area

- the individual conditions of the head of the face

- his/her medical fitness

- the period in which the wearer must use the equipment

- Wearing comfort, in relation to the conditions on the respective construction site, so that workers wear the equipment correctly for the required period of time

A Member State of the European Union recommends that:

- disposable respiratory protective equipment (EN FFP3) should be limited to situations where the concentration does NOT exceed 10 times the exposure limit and where exposure lasts for a comparatively short period of time. The softness of the mask is for comfort, but it is also the cause of mask deformation - especially during demanding work - which in turn can lead to leaks where the mask and face are tightly sealed

- A half mask with a P3 filter provides slightly better protection than the disposable respiratory equipment because the half mask has a more reliable seal to the face.

- Battery powered respiratory equipment (bonnets, suits) with a P3 filter is more suitable for longer duration or harder work.

- Full face masks (or suits) supplied with compressed air (also known as compressed air breathing apparatus) should be used if concentrations could exceed 50 times the exposure limit.

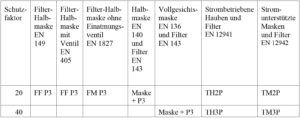

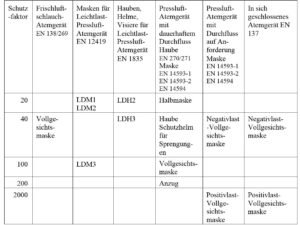

Another European Union Member State (the United Kingdom) provides tables of protection factors that can be used in selecting the best protective equipment for the situation, see Tables 8.1 and 8.2 below. The protection factors in the table also show that EN FFP3 disposable respirators are not suitable if the concentration in the air exceeds 20 times the exposure limit. Self-contained breathing apparatus (or self-contained breathing apparatus) should be used when concentrations exceed 40 times the exposure limit.

The performance of facepieces (such as filter facepiece, full facepiece and half facepiece) is highly dependent on maintaining a good seal between the wearer's skin and the mask. Because there is a wide variation in face shape between individuals, one size or type of respirator may not fit every face. Therefore, it is important that:

- a face fit test is part of the procedure for selecting appropriate respiratory protective equipment